A Survey on Fuzzing¶

Conceptually, a fuzzing test starts with generating massive normal and abnormal inputs to target applications, and try to detect exceptions by feeding the generated inputs to the target applications and monitoring the execution states. 1

Tutorial¶

Tool: AFL¶

See also

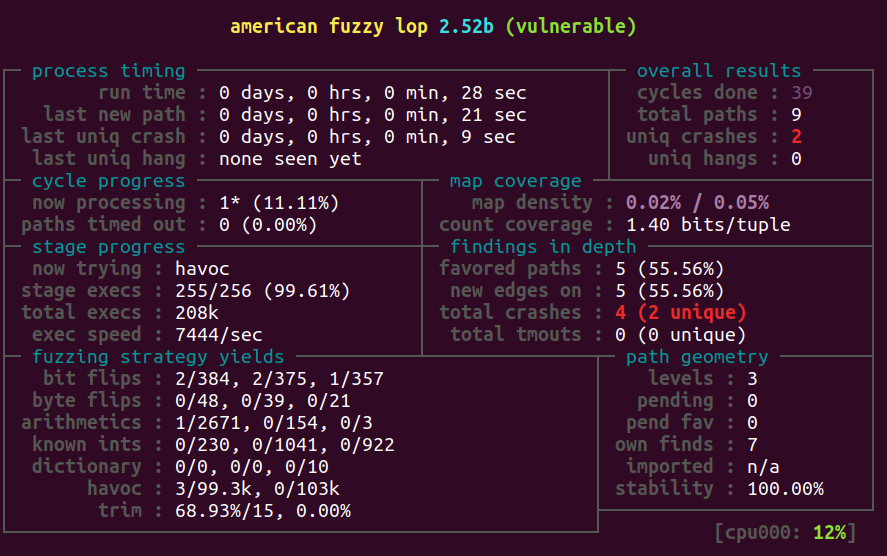

Understanding the status screen: https://afl-1.readthedocs.io/en/latest/user_guide.html

Total crashes: the number of different inputs that cause a crash. unique means the occurance of this crash takes a different execution path through the program. (not unique bugs)

Total paths: unique execution path driven by all inputs.

Hangs: timeout caused by the inputs.

Total execs: the total number of executions. (i.e. how many times the program is executed)

Map coverage: it maintains a global map where the hashed value of an edge (i.e., the pair of the current basic block address and the next basic block address) is used as an indexing key.

observed by the instrumentation embedded in the target binary

map density shows how many branch tuples it have alreadly hit (for current input), in proportion to how many the bitmap can hold (for the entire input corpus).

count coverage: indicates the variability in tuple hit counts seen in the binary.

In essence, if every taken branch is always taken a fixed number of times for all the inputs we have tried, this will read “1.00”. As we manage to trigger other hit counts for every branch, the needle will start to move toward “8.00” (every bit in the 8-bit map hit), but will probably never reach that extreme.

Edge coverage: Inputs that cover new branch(es) will be added to the seed pool.

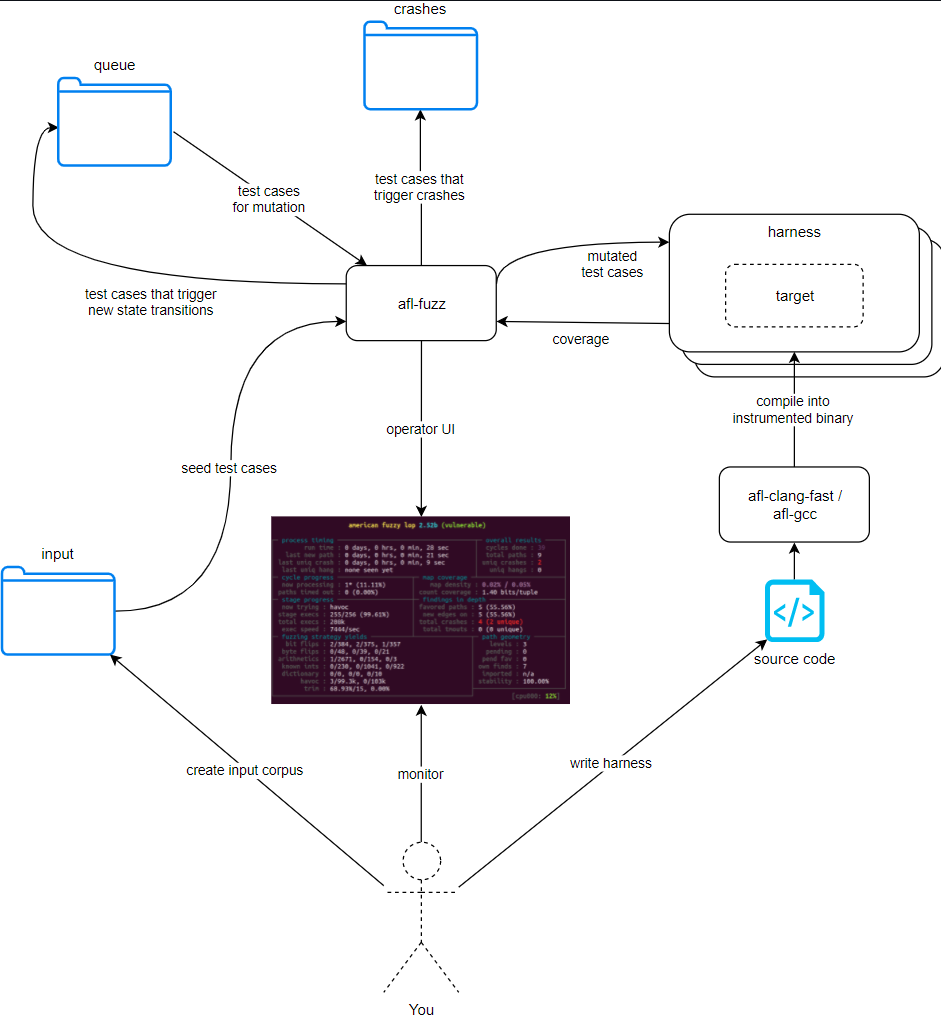

Test Harness: wrap functions to narrow down the fuzzing range

Some papers¶

Basic Notes¶

Black‐box fuzzing:

Treating the system as a blackbox during fuzzing;

not knowing details of the implementation;

Feed the program random inputs and see if it crashes;

White‐box fuzzing:

Design fuzzing based on internals of the system;

Combines test generation with fuzzing (static analysis/symbolic execution);

Goal: Given a sequential program with a set of input parameters, generate a set of inputs that maximizes code coverage

Greybox Fuzzing¶

Grey‐box fuzzing is also called coverage‐Based fuzzing. It instruments the program, instead of simply treating the program as a black-box, to trace coverage (e.g. path, edge, code, etc.)

New inputs are generated through mutation and crossover/splice on seeds;

Only a few inputs from the seed pool will be scheduled to generate the next batch of inputs (due to the limited processing capability)

For example, a single fuzzer instance can only schedule one seed at a time

The generated inputs are selected according to a fitness function;

Selected inputs are then added back to the seed pool for further mutation;

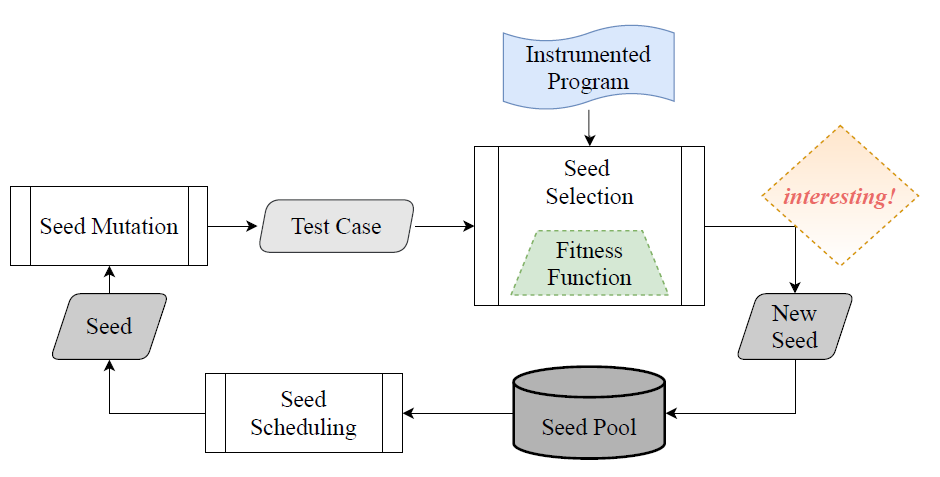

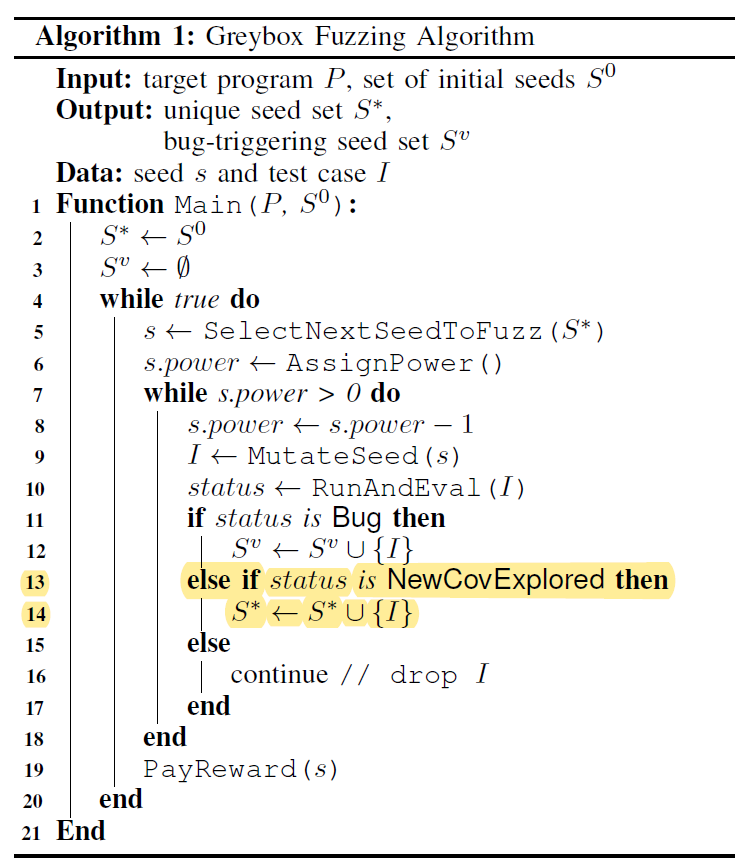

The details of a genetic fuzzing process can be described as:

Given a program \(P\) and a set of initial seeds \(S^0\); (Input)

Each round starts with selecting the next seed for fuzzing according to the scheduling criteria; (Line 5)

Assign a certain amount of power to the scheduled seed, determining how many new test cases will be generated; (Line 6)

Test cases are generated through (random) mutation and crossover based on the scheduled seed; (Line 9)

Compared to blackbox and whitebox fuzzing, the most distinctive step of greybox fuzzing is that, when executing a newly generated input \(I\), the fuzzer uses lightweight instrumentations to capture runtime features and expose them to the fitness function to measure the “quality” of a generated test case ;

Note

Test cases with good quality will then be saved as a new seed into the seed pool; (Line 13-14)

This step allows a greybox to gradually evolve towards a target (e.g., more coverage).